I have a homebuilt computer with an Antec Sonata III case and an Intel DX58SO motherboard. I really, really like both the case and the motherboard, but I’ve been struggling with a sound problem in the computer for two years now. It never bothered me enough to think about fixing it until last week, but I finally fixed it tonight and would like to share my story.

The problem goes as follows:

I use the front panel headphone jack a lot on my computer. The sound coming out of that jack was always fine until I plugged a high-speed USB device into one of the two front panel USB ports. As soon as I did that, I would always hear weird “beeps” or “screeches” in my headphones as USB data was being transferred. The problem was especially noticeable with things like external USB flash drives, my iPhone, and my AVR ISP programmer, but not with lower-speed devices like USB gamepads. It only affected the combination of the front headphones and the front USB ports — devices plugged into the rear USB ports would not affect the headphones, and devices plugged into the front USB ports did not affect the rear speaker jack.

In some ways, it was actually kind of cool to be able to hear USB data transfers, but it would get annoying when I was trying to listen to music. I did a lot of Googling about this problem, and it turns out that it’s a common problem with some of Antec’s cases (and cases by other manufacturers too). The connector you plug into your motherboard for the front USB ports has a ground pin on it. The connector you plug into your motherboard for the front audio ports also has a ground pin on it. So your motherboard provides a ground for each of these connectors. The problem is that the front port assembly on my case connected the ground pins for the USB ports and the audio ports together on its end. This created a ground loop. My understanding is that because the USB and audio connectors provide their own separate grounds through different wires, they should not be connected together at the front panel because if the two grounds differ slightly in voltage (which they can, because wires and PCB traces do have a [small] resistance), current will flow between them. This current flow manifests itself as weird sounds on my headphone jack. (I’m really not an electrical engineering expert, so if I’m incorrect or lacking in my explanation, someone please let me know in the comments below).

Here are some forum/blog postings by other people who encountered this same problem on other case models:

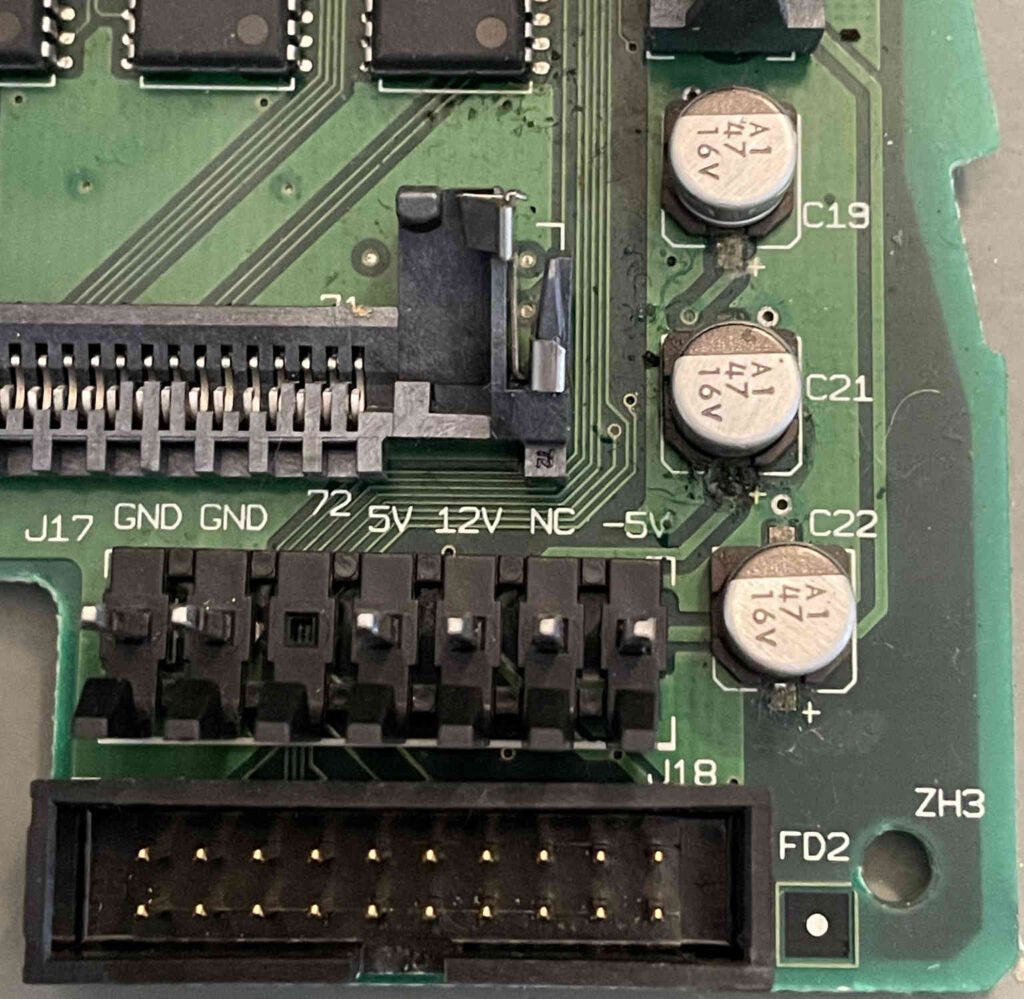

I was able to verify this by using my multimeter in “continuity test” mode. After disconnecting all the case’s wires to the motherboard, I tested the continuity between the high definition audio (HDA) connector’s ground pin and the USB connector’s ground pin. It showed continuity, so that proved that the USB and audio connectors’ grounds were hooked together somewhere inside the front panel module.

Before I did any of these diagnostics, I was writing back and forth with Antec’s customer support. I must say, Antec has excellent customer service. The people I’ve dealt with are friendly and knowledgeable. Antec customer support told me that they have this problem fixed in a newer version of the front port assembly. Meanwhile, I was waiting for it to arrive, so I decided to play with my existing front port module to see if I could fix it myself, knowing that even if I failed, a new one was on the way. With nothing to lose, why not go for it?

First, I took the air filter out (it slides out of the bottom of the front of the case). Next, I removed the front of the case. This was slightly tricky — I removed all 5.25″ devices (just my DVD burner in this case) and the external 3.5″ drive bay. With those out of the way I was able to pull off the front of the case by releasing the 6 tabs holding it on (3 on each side of the case — top, middle, and bottom). The front panel module also had a wire screwed to the chassis which I had to disconnect (interestingly, this wire is only attached to the front panel eSATA port — it has no connection whatsoever to the audio or USB ports — good thing because that would probably cause another ground loop!)

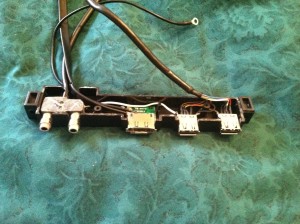

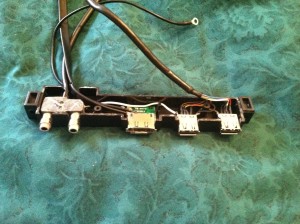

Here’s the front of the case, completely removed:

The front port assembly was attached to the front of the case by 3 screws — I removed these and then it was free to go:

Unfortunately, the front port assembly is sealed–it’s glued together or something along those lines. It’s not held together with screws or anything like that, so it’s kind of a pain to open up. It was no match for my X-Acto knife though! I was able to cut around where I could see the two plastic halves meet, and with the help of a small screwdriver, pried it apart. Amazingly, the two halves of the plastic casing stayed intact! The culprit immediately jumped out at me: there was a white wire coming out of the sealed audio assembly and soldered to the shield of one of the USB ports. I checked it with my continuity tester to be sure, but I already knew it had to be that wire, because it was the only wire that connected the USB ports to the audio ports. (This picture was taken after I had hacked it, but I tried to recreate what it looked like at first)

I grabbed my soldering iron and desoldered the white wire from the USB port:

Before doing anything else, I plugged the USB ports and audio jacks back into the motherboard, booted it up, and tested to see if the interference was still there. It was GONE! In fact, I was able to make the interference reappear by momentarily touching the white wire back to the USB port. My multimeter confirmed that disconnecting the white wire had indeed separated the audio and USB grounds from each other. I ended up cutting off most of the white wire and covering the remaining stub with electrical tape just to be safe. Somehow, even after my hack job with the X-Acto knife, the two halves of the plastic case for the front port assembly snapped back together (and stayed that way), so I didn’t have to reseal it. I put the case back together, and the audio output from my headphone jack is perfect now. I can’t hear any interference at all anymore, even if I turn my sound up all the way and plug in both my AVR programmer and my iPhone to the front USB ports.

I wish I had fixed that one a long time ago!

Epilogue:

The replacement front port assembly from Antec arrived, and it also fixes the sound problem. If you don’t want to hack apart your front assembly, get ahold of Antec customer support. They are great! I would definitely recommend getting a replacement assembly from Antec instead of hacking apart your existing one. For anyone interested, I checked out the new assembly with my multimeter, and it correctly has the USB and audio grounds separated now. The new revision also makes another change I thought I’d mention: the USB ports are also grounded to the chassis now (only the eSATA port was before — now both USB ports and the eSATA port are). So if you insist on doing it yourself, it might be wise to take that white wire you cut and use it to connect the USB and eSATA grounds together, so they will all be grounded to the chassis.

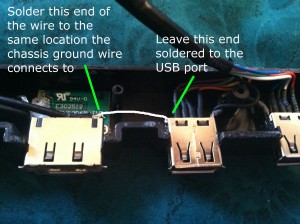

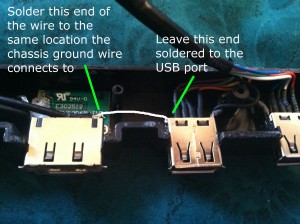

The easiest way would probably be to leave the white wire soldered to the USB port, cut it off on the audio port end, shorten the wire, and solder the other end to where the chassis ground wire connects to the little eSATA PCB. Here’s an illustration of what I mean: